I’m sure you’ll all be pleased to hear that it’ll be a short and sweet one this week ;) Nothing mind-bending or buried in lighting theory, just a simple 2 light setup with some colour! - (famous last words)

The idea behind this look for me was to create a sci-fi style of light coming directly from above. Couple that with some contrasting colour from below and a little separation behind and I’m done.

In my mind I wanted it to be smokey or hazey like those spooky 80s sci-fi movies. So either a misty night or even smoke from spaceship exhaust - think, ‘Close encounters of the third kind’. This isn’t strictly super-relevant, but early ideas like this can help you immensely when it comes to lighting a subject if you know what you’re trying to achieve first.

Let’s take a look at some of the final shots and then I’ll explain how I got there.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

I’ve include more shots from this shoot at the bottom of the article, but for now, these give you an idea of what I ended up with.

As you can see from the shots above, I feel I pulled off the look I was going for, but there are certainly a few things going on here that may not be immediately obvious to some and they are certainly worth explaining in more detail. I’ll also add, that although this setup may not be to your tastes (it is very dark after all), the techniques discussed below are well worth being aware of.

For example:

Light modifiers

Lighting distances

Colour choice

Subject separation and atmosphere

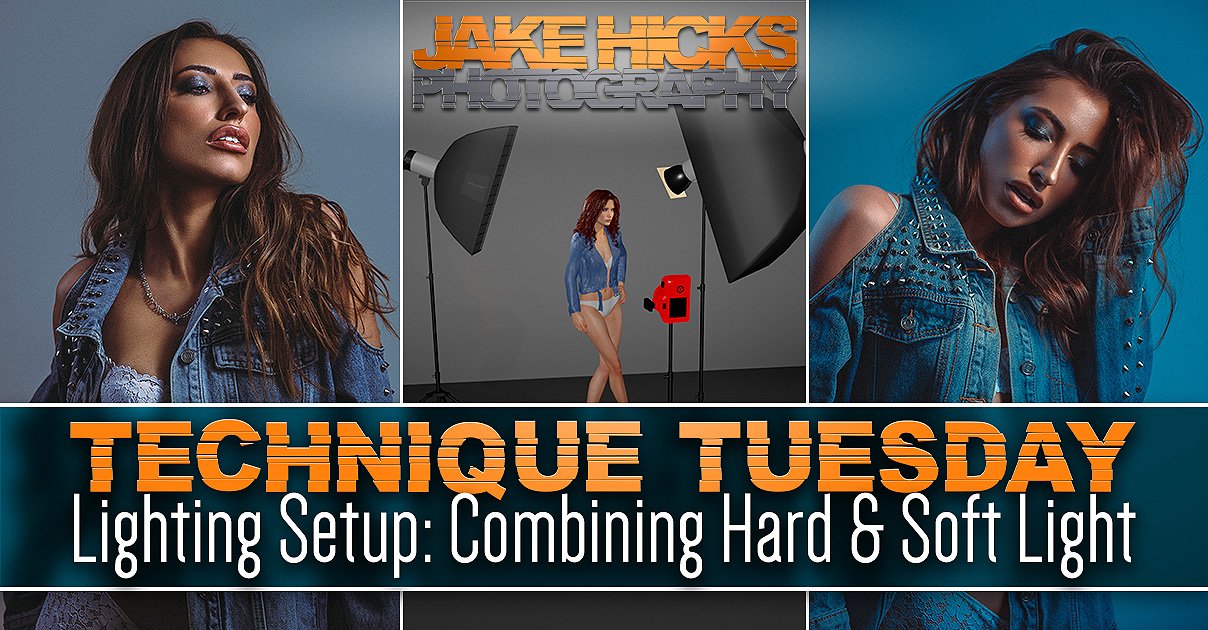

Before I go over those in more detail though, here is a 3D diagram of the lighting setup for context as I discuss things further.

Click to enlarge: Here is the 3D diagram of the lighting setup I used.

Lighting modifiers…

The keen eyed among you may have already noticed something a little different to my normal setups in the diagram above, and that’s the key light. Look again if you missed it, but I’m referring to the square light directly above the models head.

The Top Light

This light is in fact an LED light and its the modular ‘Spekular’ LED light from Spiffy Gear. If you’re interested, you can see more about it here Spekular-Spiffy Gear.

I have this modular light set up in a ring of four LED bars all joined together. Then, all I’ve done to modify this is to wrap four of my coloured gels around each of the four bars that make up the square of light above. You should get an idea of what I mean via the BTS image below.

Don’t panic though, as although this ring of light is perfect for this setup, you can still play with the same principle with more traditional lighting, albeit whilst making a couple of tweaks. For example; you could use a very small gelled soft box, ideally with a grid. Then you could suspend that directly above as well. See below:

Click to enlarge: Softbox alternative

There’s a couple of reasons I prefer my LED method and that’s firstly the power. I’ll explain lighting distances in a moment, but for the look I’m after here, the top light has to be very close to the subject. A softbox powered by a traditional strobe will be very bright even at minimum power, so this LED gives me a little more flexibility on the lower end of exposures, especially when shooting with wide apertures around f2.8 like I’m doing here. Yes neutral density gels on the lights are an option if you need to reduce brightness or even ND filters on the lens, but they come with their own issues, so the LED solution was the best fit for me personally.

The bounced light

The other light in this shot doesn’t really even have a modifier and is simply using an open reflector dish to direct the light at the models feet. What’s more important though, is where that light is pointing and onto what? On the floor in front of the model is a small white reflector and this is actually reflecting the pink light back up onto the model. Again, this is fairly simple if need-be and if you had a white floor or even a pale carpet, this would achieve a similar thing. Alternatively, just place a white sheet or towel on the floor and this will also work.

Lighting distances…

Okay so before you all think I’ve gone mad, let’s address the burning question some of you may have;

“What’s with the light firing into the floor?”

I’ll get to that in a second, but I mentioned at the start that there are a few key characteristics of this setup that are worth discussing and among them is the lighting distances. The top light is very close to the models head and as a result the power is very low. Why? The reason for this is so that the light falls off or dissipates very quickly down the body. If I was to have the light higher up, I would need to increase the power to compensate and therefore more light would be spread down the body. I didn’t want this as I wanted this to be a more intimate glow and I also wanted the bottom half of the body to be dark enough to show the secondary colour, again, this wouldn’t have happened if I’d had too much blue in the shot.

Take a look below at the two examples to illustrate what I mean. I’ve removed the dark jacket so you can better see the light on the skin, but the first image shows the light low and as a result the drop-off of light is very quick on the body. The second image has the top light a bit higher and as I’ve had to increase the power of the light to compensate for that extra distance, more light is now spilling down the body.

Click to enlarge: The blue light is low in height here and as a result we have less light further down the body.

Click to enlarge: The blue light is now higher up and I’ve had to increase its output to get the same exposure on the face. This has also resulted in more light falling further down the body.

Stay with me…

You should clearly be able to see the difference, even though I’ve only moved that light a matter of inches. When using lights in close quarters like this, accurate placement is crucial to get the desired look, so don’t be afraid to make small adjustments and even consider getting the model sat down if you don’t have a high enough ceiling to get what you’re after.

Further reading: As the more experienced among you will know, this principle of moving the light closer or further away and adjusting the power to compensate is all part of the ‘inverse square law’ theory. It states that measured light intensity is inversely proportional to the distance squared from the source, or in English: every time you double the distance from the light, you quarter the light power it receives. This is very dry and impractical reading for creatives in my opinion, but we all learn differently so by all means read up on it. Just know that you don’t need to memorise the physics formulas to take better photos, just be aware of the light fall off, especially in tight quarters like this.

Why is it important to have the light so close?

The reason for this is as I explained and that’s the shadow areas. Contrary to what the 10 minute YouTubers will tell you, you really shouldn’t just blast your subject with tons of different colours and then edit them in post. If you only remember one thing from this article, make it this:

You can only apply a coloured gel to a shadow

The reason this is so important is so that you maintain clean, clear and bright colours. In general (and there are exceptions), you shouldn’t mix coloured light and many people who start playing with gels get washed-out and insipid colours because they mix them. Maintaining complete control of the light on your subject will enable far richer colours and having your lights very close like I’ve shown you above ensures that multiple lights don’t contaminate one another on the body.

….so why the hell is one of the lights pointed at the floor?

The reason I’ve done this here is twofold. Firstly, I’m almost breaking that rule I just gave you in the section above. By bouncing the light into the floor, I’m effectively doubling the distance that light has to travel before it hits my model.

“Jake, you literally just said the lights have to be super-close?!”

The reason I’m doing it here is because I can’t get my bottom light out of shot and placed directly below the model. I wouldn’t need to do this if my model was stood on a sheet of glass and I could position the light directly underneath her just like I have the light positioned above her.

I want the light to appear like it’s coming out of the ground and from below her. With the top-light, I can achieve that look by bringing the light directly above. I can’t do that on the bottom because the floor is in the way.

Ordinarily you’d set up a fill-light here, maybe a small softbox on the floor for example, but I can’t just use a regular fill-light to get that same look because it has to be positioned in front. The light wont look like it’s coming from below. Take a look at the diagram below to see what it would look like if I had done that.

Click to enlarge: Alternative setup with the softbox below

The issue I explained earlier is happening against us here. The light has to be close so that it will fall off up the body, but by bringing it so close, you end up with a hotspot at the bottom, plus I want the light to feel like it’s emanating from below…. not just looking like it’s sat in front of her. If I bring that light further away to reduce the hotspot, we are now fully lighting her from the front and not from below at all.

To counter this look, I simply fired my pink light into a reflector on the floor below the model. The light now feels like its coming up the body, plus the light has travelled far further to do so and this results in a more gradual and smoother light without the hot-spot.

-Like I said at the start, ‘famous last words’ that one of Jake’s coloured gel setups would be ‘short and sweet’. ;)

Colour Choice

This topic isn’t particularly tricky to discuss and essentially you can play with any two colours you like here, but there is one area I’d urge you to consider, and that’s ‘colour dominance’.

All colours have a certain ‘visual weight’ to us when we view them. Take a look at the three colours below. They are all technically the same brightness in terms of luminance, but for many, the yellow will appear more dominant, even though it may not be technically brighter.

There are entire books dedicated to these ‘dominant and recessive’ colour theories and although very interesting, I don’t want to get too lost in the weeds with it here. If you’re interested then there are tons of other articles on my site that discuss it in terms of photography, so have a look through my archives when you have a spare week off.

The key point I want you to take from this, is to consider what colours you choose for your top light and bottom light carefully. Your top light or key light should always be the dominant light and in my shot I’ve chosen a pale blue colour over the deeper pink from below. My advice for you here, is to just trust your eyes. If the colour you’ve chosen for your bottom light feels more dominant, it likely means it is. Take the time to swap them around and you’ll instantly know which looks better.

Still think I’ve been smoking too much bat-guano? The image above is the exact same 3 coloured squares from before, but with zero colour saturation. Voila! They are all the exact same brightness!

This is an extremely powerful and advanced tool in scene building, as when using colour, it isn’t just a matter of checking the light meter to get the ‘correct’ exposure, consideration should also be given to the colour dominance as well. Can you see why black and white shooters can phone-it-in now?

Subject separation and atmosphere

Again, this is going to be down to personal preference, but let me explain my approach and what I wanted to achieve with this. As I stated at the start, I was going for a retro sci-fi vibe and I wanted my model to appear like they were emanating from the smoke in some way. Although I’ve played with thick smoke in the past, it can be a little hit-and-miss in terms of it looking too cheesy or over the top. For this shot, I went for a hazy look and this helped me in a couple of ways.

Haze is different from smoke in that it doesn’t take the three dimensional shape that smoke does. Think of haze as simply thick air or atmosphere and by using haze, you eliminate it becoming its own character in a shot. This is getting a little esoteric I know, but when people see this shot, they shouldn’t necessarily immediately notice the haze like they would if I’d used smoke.

The other core aspect to using haze here, is that you are able to see light in the dark areas of the shot. For example you can see light clearly in the space above the models head, but more importantly, you able to see some light behind her.

Why is this important?

The reason this is so useful here, is because I’m trying to separate a black coat against a black background. This is almost impossible to do with such a dark image ordinarily, but thanks to the haze in the room behind her, we are able to see the model separated against the backdrop as the light is illuminating tiny amounts of haze.

This is a very useful trick to be aware of and cinematographers do this a LOT in shows and movies where they need to show character separation at night without being able to illuminate the background. Simply add haze to the shot and your subject will immediately jump forward in the scene. Think of this as ‘volumetric lighting’ and once you start to get to grips with it and understand its potential, any number of difficult lighting scenes become far easier.

The final shots

Below you can see all the images that made it through the final editing process. Simply click on any of the shots to enlarge them.

Closing comments

Ironically, the shot I had in my minds-eye prior to shooting (a shot of the subject looking up at the light emanating from above), didn’t actually make the final cut. I shot it and played with it, but ultimately it felt boring compared to the others I captured. You can take a look at it below, but the reason I’m sharing it here is because I think this ability to be open to alternatives is an important part of the creative process.

Absolutely have a vision in your head before you start shooting, but don’t be completely beholden to it. Be open to ideas and alternatives on the day, be willing to try different modifiers, colours and poses, get an opinion from the other team members and always be willing to try something new. You’ll often find that your creative process far outstrips your creative vision and this is a fundamental part of growing as a creative.

Good luck with your shoot if you’re giving this one a go, by all means feel free to share your final results on my community page to get some free feedback. I do a -Share-a-Shoot- every Monday on my Facebook Page, so I look forward to seeing your work there soon.

Featured model: Simone Stocks

Thank You

As always, thanks for checking out this article and spending a little bit of your day with me here. I hope you found it useful and if you left with a little more knowledge than when you arrived, it’s been worth it.

If you have any questions or comments, or if something doesn’t make sense, by all means fire-away in the comments below and I’ll do my best to answer what I can. Thanks again and I’ll see you in the next one.

Don’t forget to sign up to my newsletter to be sent all of these photo tips and techniques articles every month in case you miss one.