Trigger Warning: Yes these shots are of a young lady in her underwear and no that is certainly not necessary for this setup to work. Truth be told; we were working on a separate shoot and model, Grace kindly allowed me to quickly grab some of these shots to illustrate this article and lighting concept for you. The simple shots here are really only to show the lighting technique behind combining hard and soft light and what benefits it can have. Once you understand the reasoning and benefits of lighting in this way, you’ll quickly realise just how far you can take it and how versatile it can be.

Like I mentioned, this hard-&-soft-light-combined is a very simplistic concept at its core and once you see it in practice, you’ll quickly see how you can develop it further with other modifiers and setups. So although I don’t use this particular method myself any more today, I used it a ton when I started to play with it many years ago for headshots and hair campaigns. To understand the benefits of lighting with hard and soft light combined, let’s first look at what isolated hard and soft light means to us as portrait photographers.

Lighting a portrait with soft light

We all likely know what a soft-light portrait looks like, but let me quickly check we’re all on the same page with it. A portrait lit with soft light is generally lit with a large light source, like a big soft box or even a large window light. This large light source wraps the subject in light and provides a very flattering and beautiful light as a result of it filling in any unsightly lines and creases on the subjects face. Take a look below at an example of a soft-lit portrait taken with a medium sized softbox.

Click to enlarge:

Click to enlarge:

Click to enlarge:

As you can see in the setup diagram above, this softbox is in nice and close to the model to allow for maximum wrap of light on the subject. It’s also worth noting that all the shots taken for these example images had a small gridded strip softbox to camera-left behind the model. You don’t need this for the setup to work and you could easily substitute this light for any number of other modifiers including another simple gridded dish if you had one. All this back-light is doing is providing a small amount of separation on the models darker side to add depth against the darker background. That will be even more apparent in the hard-light version of this in a moment.

It’s also worth noting that this is shot against a white wall and any light you see behind the model is from that large softbox. This distance of model-to-wall will be more important later on as we take advantage of that fall-off of light from the key softbox.

Some of the properties and qualities of soft light portraits:

Very flattering light on skin

Can be flat and lacking in contrast

Even tone and exposure across the subject

Minimal bright highlights and overly dark shadows

Easy to setup and use

Can leave hair and clothing looking flat

Lighting a portrait with hard light

Now let’s take the same portrait but with a hard light source. Again, just to check we all agree on what a hard-light is when lighting a portrait, it can be best described as a small light source in relation to the subject. There are plenty of these hard light modifiers and even a flash with no modifier at all is a very hard light source. Other examples include a snoot, a gridded reflector dish, optical snoot and even a small reflector dish with barn doors is a hard light. Take a look below at the example shots taken with a simple gridded reflector dish.

Click to enlarge:

Click to enlarge:

Click to enlarge:

This is exactly the same setup as before, the only thing that has changed is the key light has been swopped out for that small gridded reflector dish.

Some of the properties and qualities of hard light portraits:

Very contrasty light

Deep, dark shadows and very bright highlights

Small pool of light

Can be unflattering on skin as it exaggerates any spots, lines and creases

Tricky to use this lighting as good posing is crucial

Gives hair and clothing strong contrast and shine

The benefit of getting the best-of-both

As we can see from the two basic tests above, hard and soft light produce drastically different results, but so what?

Soft light is more flattering for skin; so you should just stick to that right?

Yes, soft light is arguably a more flattering light to use on skin and that is down to its ability to fill in shadows and reduce contrast overall. This does have a big downside though and that is that it can leave portraits looking a little flat.

We came across this problem years ago when we were shooting a lot of hair campaigns and hair competitions. We had to light people and their skin, and to make them look good we started out using soft light to do so. The problem was, this soft light left the clothing and more importantly the hair, looking very flat and not beautifully shiny like it was in reality. We could either light the whole shot in hard light to make the hair look great, but the skin and model wouldn’t look ideal. Alternatively, we could light the image with soft light to make the subject look great, but in the process the hair always ended up looking flat and limp as a result.

Hard and Soft Light Combined

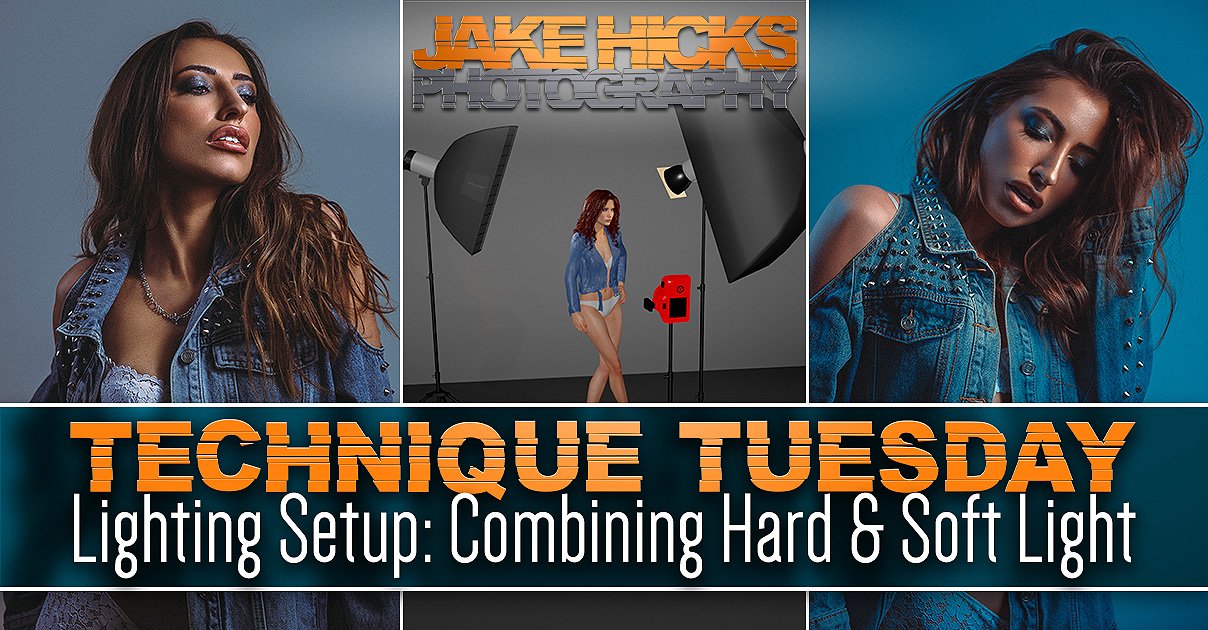

It was this dilemma of trying to blend the best-of-both that led me to simply combine both lights into one. Thankfully, this is actually far easier to do than you might imagine, plus it also has some remarkable benefits that you simply cannot get any other way or with any other modifier. Take a look below at the next set of shots with my hard and soft light combined setup.

Click to enlarge:

Click to enlarge:

Click to enlarge:

In the setup image above, you can now see that both the hard and soft lights are on set and they’re actually in the exact same places they were in the earlier setups, its just that now, they are both lighting the subject. Note: Just incase it’s not immediately obvious, the gridded reflector is stood directly in front of the large softbox in the diagram above.

At first glance, some of you may not be able to spot too much difference between the simple soft light shots from earlier and these hard and soft combined shots. To be fair, that is kinda the point. The soft light is clearly the dominant light source here and we are just trying to take some of the qualities of the hard light and add to that. For example, we really just want a little extra kick of contrast to add some additional shape and form to not only the models features, but the models hair and styling too.

Take a look again at the closeups of the two setups now side-by-side below. The image on the left is the softbox alone and the image on the right is with the addition of the hard light. Look at how the skin, eyeshadow and lips has that additional contrast, pop and shine to it and the same applies to the hair here too, even though this hair has no additional product in it.

Click to enlarge:

Hopefully you can now start to see what I mean when I refer to the ‘best of both hard & soft light combined’ and hopefully you can also start to understand the benefits of this concept too. Yes this is a basic concept and lighting setup, but in all honesty, if you can even see what I’m referring to in the nuance between these shots, then it does show you have a far broader understanding of being able to read light than many.

In the image above you can see the two catchlights stacked one behind the other. This is important as failing to do so will result in ugly double-shadows (note the only image I could find showing the catchlights was 10 years old, so I apology for the quality).

Important things to consider

We looked at the basic setup in the diagram above, but what are the things we need to consider when setting this up?

Background

Firstly you’ll notice that I placed the model a little way off of the wall. This was to allow the hard light to illuminate her, but not also hit the wall behind. As a result, the only light hitting the back wall is the soft light of the softbox. You can even do this same setup with the light being straight on to the model (i.e. coming from camera), but you just need to watch that hard light shadow on the wall behind the subject.

Stacking

Next, you’ll want to be pretty strict with how you place the hard and soft light and I strongly recommend that you place the softbox directly behind the hard light and NOT just off to one side. There are a couple of reasons you want to do this, but paramount among them is the fact that you’ll only get one set of shadows if you stack them in this way. Failing to do so will result in a far messier image with potentially overlapping shadows. It’s this very clean approach to lighting that makes it almost impossible for others to spot when you are using this technique, as if done correctly, you only get one set of shadows and it appears like you are only using a single light.

Exposure management

Last (but by no means least), you’ll need to manage the exposure. This seems glaringly obvious I know, but managing and adjusting the exposure of these two independent lights is actually one of the key attributes of this setup that makes it so versatile and powerful. With these two lights in place, we get to choose how much power each of the lights give. Do we want a lot of soft light and only a little hint of contrast from the hard light? We can do that. Do we want a lot of contrast and only a little fill-light in the form of that soft light? We can do that too. For me, this is what makes this setup so powerful and having the ability to adjust the power of these two lights independently is a unique quality that no single lighting modifier can give you. Once you start to play with the variety of lighting looks these simple two lights can provide, you’ll soon realise just how powerful this setup can be.

Taking Hard & Soft Combined Further…

The following is a slightly more advanced setup that simply builds upon the basic principle of the previous hard and soft combined setup. In fact, nothing changes too much at all beyond adding a single gel to one of the lights and adjusting our camera, and although that seems like a minor change, the look is completely different. Like I mentioned, this is just an advanced version of the basic setup explained above and I’m only including it here as I know regular followers of my work are pretty experienced in the studio. Feel free to skip this next bit if you like.

Hard & Soft Combined with Kelvin

Take a look below at the resulting images of this new setup and then I’ll explain how I got them.

Click to enlarge:

Click to enlarge:

Click to enlarge:

What the hell is going on here Jake?! It appears you’ve added an orange gel in the diagram above, yet the resulting images are blue? What gives?!

Yes, the eagle-eyed among you may have noticed an orange gel on the hard light in the diagram above. That gel is in fact a CTO gel (colour temperature orange gel) and that is not to be confused with a regular orange gel. With that CTO gel in place on the hard-light, I then adjust the Kelvin on my camera (white balance) to compensate for the extra orange in the shot and ‘boom’, we’re done.

Breaking it down

If you’re unaware, a CTO gel is designed to reproduce the colour of tungsten light when you fire a flash through it. A tungsten light is an incandescent light that is essentially super-heated tungsten metal. You probably know that hot metal glows orange and that is where the resulting warmer colour comes from. To put this colour into a number, we put it on a Kelvin scale that many of you know as white balance. On that scale, daylight and flash are around 5500 Kelvin and tungsten is about 3000 Kelvin. Don’t get too hung up on the exact numbers as they are arbitrary and vary between cameras and lights, just know that flash is cold and blue, and tungsten is warm and orange.

Click to enlarge: Here is my quick example of white balance and Kelvin and how it relates to tungsten and flash. You can see how in the images above, an image lit by flash will go bright blue when shot at a colder Kelvin value. Conversely, a tungsten shot will appear very warm when shot with a higher Kelvin value similar to that of flash.

I place a CTO gel on my hard light which gives it that warmer, tungsten colour to it. I now want to counter that orange look on my model, so I reduce the Kelvin on my camera down to around 3000 Kelvin so that my model now appears to be lit with white light. Next, I turn on my softbox, remember the softbox doesn’t have any gels on the light so now the softbox light appears blue in shot thanks to my lower Kelvin value in my camera.

Like I said, I was wary of including this, because whenever you write this stuff down, it always sounds far more complicated than it actually is. Give it a go, it’s pretty simple once you’ve done it once.

What’s interesting about this setup is now that I’ve essentially split the two lights into these two colours of white and blue, you can now see exactly what each of them is doing in shot. Everywhere we see blue in the image is where the softbox is lighting and everywhere we see white light in the shot is where the hard light grid is falling.

As I mentioned at the start of this section, this is a little more advanced and will likely require you to play about with varying values to get the look you’re after as different lights, cameras and even gels will have varying colours when it comes to Kelvin so be prepared to play around a little.

Featured model: Grace Ellen McEwen

Good luck with this one and definitely have a play with it next time you have a portrait shoot lined up. Like I said, this is a great setup to show the power of combining both hard and soft light in the same shot and once you have this basic concept dialled in, you can scale it up to other light combinations. You may even like to try this alternative that enables you to combine hard and soft with a single light AND light more than just a head shot. To learn more, take a look at this Using a Single DIY Globe Modifier for Simple, Stunning Portraits

Thank You

As always, thanks for checking out this article and spending a little bit of your day with me here. I hope you found it useful and if you left with a little more knowledge than when you arrived, it’s been worth it.

If you have any questions or comments, or if something doesn’t make sense, by all means fire-away in the comments below and I’ll do my best to answer what I can. Thanks again and I’ll see you in the next one.

Don’t forget to sign up to my newsletter to be sent all of these photo tips and techniques articles every month in case you miss one.