So before my regulars start to suspect that I’ve been kidnapped and forced to write this against my will, yes this is indeed a lighting setup article that involves natural light! But don’t worry, we’ll quickly skip over the easy, beginner daylight setup and move on to the adult version that combines gels and strobes later on. So, if you’re suspiciously U.V. averse to the point where you could star in an Anne Rice novel, don’t worry, stick around to the end and I’ll have something a little more visually engaging for you there.

TRIGGER WARNING: Yes I’m calling a large sheet of diffusion a ‘scrim’ and not a ‘silk’. What’s the confusion between silks and scrims? Historically scrims are large sheets of dark fabric that reduce the power of fixed-brightness HMI’s and silks were the white versions. Today though, as nearly all lights are adjustable in power thanks to dimmers, we photographers tend to use the blanket colloquial term ‘scrim’ when referring to large sheets of diffusion. Theatres actually use the same wording for similar semitransparent sheets of white fabric and it may be where the confusion comes from. But rightly or wrongly, if you ask for a scrim on a photoshoot in any studio I’ve worked in, someone is gonna grab you a large sheet of diffusion. Plus, if you search for scrims on photo-sites, you get white diffusion. I apologise in advance for calling the large sheet of white diffusion a scrim for the rest of the article.

What is a scrim?

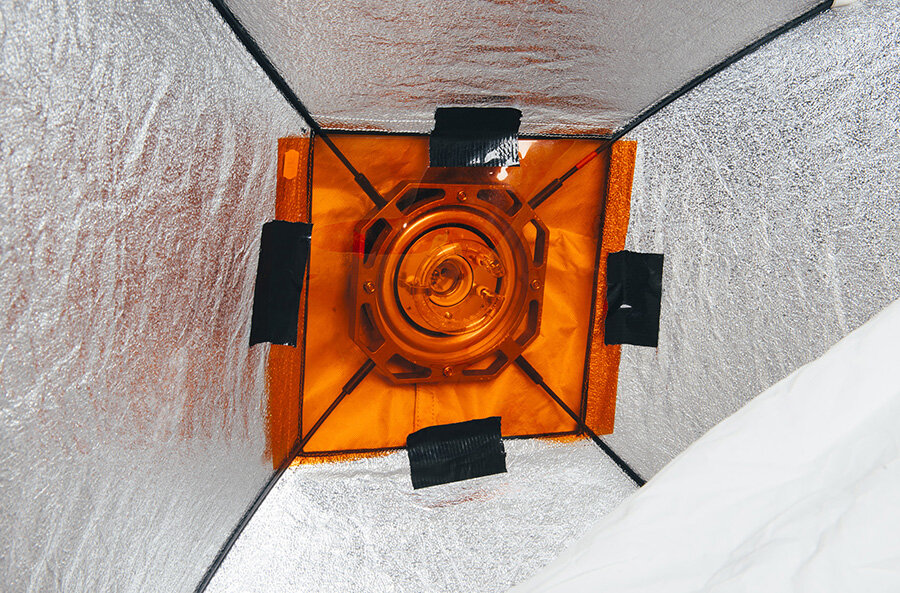

Before we get into the setup, let’s first take a look at the core lighting modifier I’m using here, the ‘scrim’.

To those not aware of what this is, it’s essentially a sheet of fabric that diffuses the light that passes through it. This is very similar to the front of your softbox, just on a far larger scale. Scrims can be purpose built frames like the one I use here, or they can simply be diffusion material strung between two points.

Scrims are often used by videographers and on larger film sets when a wider area of frame needs to be bathed in soft light. This comes in extremely useful when dealing with daylight that is ordinarily very bright and harsh on days with limited natural cloud cover.

The Scrim I use…

This is the large one that I use for outdoor diffusion with the sun, but it’s also just small enough for me to use in the studio when I want a softer, larger light than a softbox.

The 150cm x 200cm is actually just small enough to also use in many home studios too, and I have done so on numerous occasions. The frame/stand that it comes with allows me to position and angle it exactly where it’s needed, without having to use additional stands and booms to hold it in position. This was also one of the cheapest scrims that I found for its size and I got it here in the U.K. at Essential Photo. If you’re interested, here’s the link 150x200cm Scrim with Stand and Locking Wheels.

What does a scrim actually do?

Like I mentioned above, its like the diffusion cover on the front of your softbox, its just that a scrim is often used in conjunction with the sun, although I’ve used it more often to soften lights in the studio. For this article though, I’ll be using it outdoors to soften and diffuse natural light.

Why do you need to soften and diffuse the sun?

The simple answer is that you don’t have to soften the sun and many people like the look the bare sun gives. Unmodified natural light can be extremely hard and unforgiving on your subject though, and hard light is often light that is small in relation to your subject. The sun is a tiny spec in the sky in relation to us, thus making it one of the hardest light sources available.

Let’s look at what a bare sunlit portrait looks like…

Below are a couple of portraits taken with just the bare, unmodified sun.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Let’s be honest, photography doesn’t get any simpler than this. The sun is out, hold your camera in the right direction and BOOM! A great looking shot. If you’re after a quick fashion shot or a low-budget New York editorial, you’re done and extremely hard-light like this offers a few key elements we can use. It’s a very contrasty light with deep, dark shadows and bright, piercing highlights. This is often a nice look for fashion, as it makes colours pop and textures stand out, but it does have some downsides. The contrast can often be too much and if you’re not careful, important elements can be lost in the darker areas of frame. Harsh light like this can also be unforgiving on the subject too. Models will often understandably squint into the sun and if your posing and angles aren't spot-on, the subject will not look great, especially if they’re not a ‘model’ to begin with.

Let’s add a Scrim to that…

Okay, so we have the bare sun on set, we aren’t overly happy with the poor model squinting at us and we’d like to open-up some of those darker shadows too. The easiest solution without needing to add supplemental lighting, is to bring in a scrim.

Now let’s place our large scrim in front of our model and see what the shots look like by comparison.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Yes, I’ve been very arty-farty by including the scrim in shot here and of course that is totally not necessary, I just personally prefer the multiple extra layers of depth both in the foreground and background the colour and surroundings add to the shot.

With the scrim in place, we can immediately see the light on the model is far softer and certainly a little more flattering. Plus, the poor model can now open her eyes when she’s looking at the camera.

I’m far from a natural-light shooter, but I have to admit, I actually really loved this setup a lot. The colours and contrast from the two areas of light thanks to the harsh light behind and the softer light in front from the scrim look fantastic. So much so, I actually felt a little guilty at how easy this is to achieve. After all, I just went outside and set up my scrim!

Click to enlarge

Cloudy day…

For those wondering what this setup looks like when the sun goes behind the clouds, here’s a shot of the exact setup above, but all that’s changed here is some clouds covered the sun.

I obviously had to adjust my camera settings to accommodate for the far darker shot, but it does show how much flatter the image is without that contrasting light to make it pop. You can somehow tell that this image was shot on a cloudy day, regardless of scrim or not.

Taking it further…

So we had some fun with daylight and our camera set to ‘P for professional’ earlier, now let’s consider adding some more creative elements to give our shot another layer of interest.

Click to enlarge

Adding a strobe

For this slightly more involved setup, I’ll be adding a strobe to the set. This strobe will also have a gel attached and we’ll then try to balance the exposure and colour of both daylight and flash in the same frame.

Everything else has stayed the same and scrim is still diffusing all the light that is falling onto the model. To counter that, I now wanted to add back a hard-light element, but really only on the subjects face. To do this I brought in a strobe with a bare dish and barn-doors. This bare light will be a harder light source than the now diffused sun and that will result in me being able to add some more dimension to the model with the help of shadows.

In the BTS image I’ve provided here, you should be able to see the strobe in the upper right corner. You can also see the barn-doors attached and the colour temperature orange gel attached too. I’ll explain that in a moment, but for now, look again at the position of both lights. The sun is one light and that is off to camera-left being heavily diffused by the scrim just to left of frame here. To contrast that light, I’ve positioned the hard strobe with CTO gel to camera-right so as to cut across the frame without directly hitting the background. You can see it striking the backdrop a little here, but I subsequently adjusted that light to try and avoid that as best as I could later on.

The final shots

I’ll share some of the final shots here now so that you can begin to understand the setup more clearly as I explain it further. Take a look at some shots with both the scrim and strobe at work.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

A few of you looking at these initial shots will likely have a pretty good idea of what’s going on, but let me now explain it a little further. Before I do that though, look again at where you think the strobe is falling on the model and where you think the sunlight is falling. You should clearly see the now brighter strobe light on the models face and the resulting shadows it’s casting. These shadows on the opposite side of the face are now filled by that beautifully soft scrim light and it’s actually this subtle balance of exposure that is the tricky part to manage.

So how come she’s blue?

At this stage you could wrap this article up. If you wanted to shoot this yourself, you can of course just scrim the sun, then add a strobe to the shot and call it a day. But no self-respecting strobist is going to pass up an opportunity to add some colour to that setup, right?

As I mentioned above, I’m simply placing a Colour Temperature Orange (CTO) gel on the strobe, and that’s it, there’s no other colours or lights being used here. So how come she’s blue?

The trick to this setup is to manage your cameras white balance so as to create that extra colour contrast between sun and strobe. The CTO gel is essentially making the strobe bright orange and that strobe is shining light on the models face. To counteract that orange colour on the models face, I adjust my cameras white balance. For these shots I was shooting at around 3000-35000K.

By shooting at a far cooler Kelvin like this, I am essentially making the image very blue wherever daylight falls, but where the models face is already orange from the CTO gel, it cancels the two colours out, making the models face a more normal tone. Granted, the final images here are far from a ‘normal’ tone, but I’ve opted to show a mix of both the warm orange and cool blue in the shot over cancelling one of them out.

Second set

I wanted to mix up the styling a little, so I asked the model to change into a different outfit. There was one technical reason I wanted her to do this too though, and that’s the blue legs from the previous look. The CTO strobe is only shining onto her face and anywhere not being hit by that strobe was being made blue by the very low Kelvin value. As a result, her legs were bright blue and I wanted to try a look that wouldn’t highlight this quite so much.

Take a look at some of the subsequent shots after she’d changed…

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Again, I really love how these look. This is still a super-easy setup though and sunlight is such a dream to work with for portraits. Daylight seemingly fills every single pixel with data and even seemingly dark corners or under objects still have some light reaching them thanks to daylights ever-invasive nature. If you’re a studio shooter used to dealing with flash indoors, you’ll find this quick and easy setup very rewarding to play with.

Important points to consider

The first setup I spoke about in this article really doesn’t need much explaining. You simply go outside on a sunny day and point your camera towards the subject. If you want to take it a step further though, don’t hesitate to add a scrim to the setup to really give your shots another dimension. I promise, you’ll instantly fall in love with the look it provides.

For those looking to take things a little further by adding strobes and gels, there are a few potential pitfalls that I’d caution you to consider before doing so. Yes this setup looks simple with only one additional strobe, but it only appears that way if you’ve managed a couple of key areas correctly first.

Hard & Soft

I talk about managing the creative potential of combining hard and soft light all the time in my courses and workshops and this setup is no different. You can only get the visual impact of that colour contrast if you manage the lighting contrast first. Remember, we are taking the sun (a very hard light) and making it a soft light thanks to the scrim. We can now contrast that soft light with an additional hard light courtesy of our strobe. This setup simply will not work without that scrim to firstly soften the hard sunlight.

ISO 31 - Aperture f2.0 - Shutter Speed 1/4000!

Managing exposures

Sadly, I’ve left the hardest part ‘til last. This may not be an issue for you and your kit, but for me, the hardest part of this entire setup was managing the extreme brightness of the sun. Yes the scrim takes a couple of stops of power away, but even still, when I added my strobes, I found it hard to overpower the sun with my 500w strobes. If you have more powerful flash heads, you should be fine, but first let me explain the issue.

We normally manage the power of the sun in our cameras via shutter speed. The ISO is usually kept low to keep the noise to a minimum and the aperture is used to get the desired depth of field we want. With that in mind, we then adjust the shutter speed to reduce the power of the sun.

Remember that shot I showed you at the start of the article that was just bare, hard sunlight? That was taken with the following camera settings: ISO 31 - Aperture f2.0 - Shutter Speed 1/4000!

In case you’re new to planet Earth, that’s a lotta light! Now try and add your strobe to that and overpower it. Spoiler Alert: It’s not going to happen.

The biggest issue here is most cameras will really only sync to flash with a max shutter speed of around 1/125th to 1/250th at best. Any faster and the images start to get black bars across them as we photograph the shutter. If we shoot at those lower shutter speeds, we’ll need to compensate for the brightness by drastically adjusting our aperture, and it’s been a few years since I shot at f64!

ISO 100 - Aperture f2.0 - Shutter Speed 1/1000.

HSS

So how do you overcome this extreme brightness issue? Thankfully most strobes today come with HSS (High Speed Sync). This technology now allows you to shoot with a strobe at far faster shutter speeds by somehow pulsing the chip with the required light as the curtain moves across the frame. It’s actually been a few years since I was told how HSS works, so please, if you’re interested, seek a second opinion and if anybody in the comments wants to elaborate, I’d be most grateful.

Regardless of the nerdy specifics, HSS works and the HSS on my strobes enabled me to get these shots with both the strobe and daylight being the desired exposure. The final set was shot with these settings: ISO 100 - Aperture f2.0 - Shutter Speed 1/1000.

Like I said, this is likely the biggest stumbling block for some of you based on the kit that you have. Check to see if your flash has HSS and if so, you’re good to go. If not, you may need to make some sacrifices to combine both flash and sunlight. One way to get that sunlight power down and thereby lower your shutter speed so you can use your strobe is with ND filters. Reduce the amount of light coming into your lens with neutral density filters and then you can lower you shutter speed. Failing that, you’ll have to stop your image down via the aperture and shoot at something like f11 or f16. It’s not ideal, but definitely doable.

Closing comments…

Like I’ve been saying throughout this article, these setups are a lot of fun to play with, and from the simplest sunlight and scrim to the more involved strobe and sun combined, you’ll get scores of great shots to play with straight away.

One last thing for my studio-dwellers, remember that the big natural strobe in the sky is changing all the time. Clouds are moving, the sun is moving (technically we are, but you get my point), keep a constant vigil on the exposure and adjust it accordingly.

If you don’t have a scrim yet, definitely consider getting one as although I bought mine for one specific purpose a while ago, I’ve ended up using it way more than I thought I would for other setups. If you’re tempted, here’s the link to the one I have again at Essential Photo here in the U.K.: 150x200cm Scrim with Stand and Locking Wheels.

Lastly…

If you’re feeling super-adventurous, sunlight is a great excuse to dig out the old film camera and have a play with that too!

Images below shot on my old medium format Pentax 6x7 with 90mm f2.8 lens.

Featured model: Isabella Besque

Thank You

As always, thanks for checking out this article and spending a little bit of your day with me here. I hope you found it useful and if you left with a little more knowledge than when you arrived, it’s been worth it.

If you have any questions or comments or if something doesn’t make sense, by all means fire-away in the comments below and I’ll do my best to answer what I can. Thanks again and I’ll see you in the next one.

Don’t forget to sign up to my newsletter to be sent all of these photo tips and techniques articles every month in case you miss one.